Welcome! Can I Interest You in an Excerpt?

Thanks for visiting The Gray Market, everybody. Below is a semi-substantial chunk from something longer I’ve been working on. The topic is Damien Hirst and his (in)famous 2008 auction at Sotheby’s London, titled Beautiful Inside My Head Forever. It fits in well with the ethos of this blog by virtue of examining some of the economics, incentives, and business practices driving the sale (and Hirst’s career in general). Figured that made it as good an inaugural post as any other. Hope you enjoy while I start generating original blog-specific content.

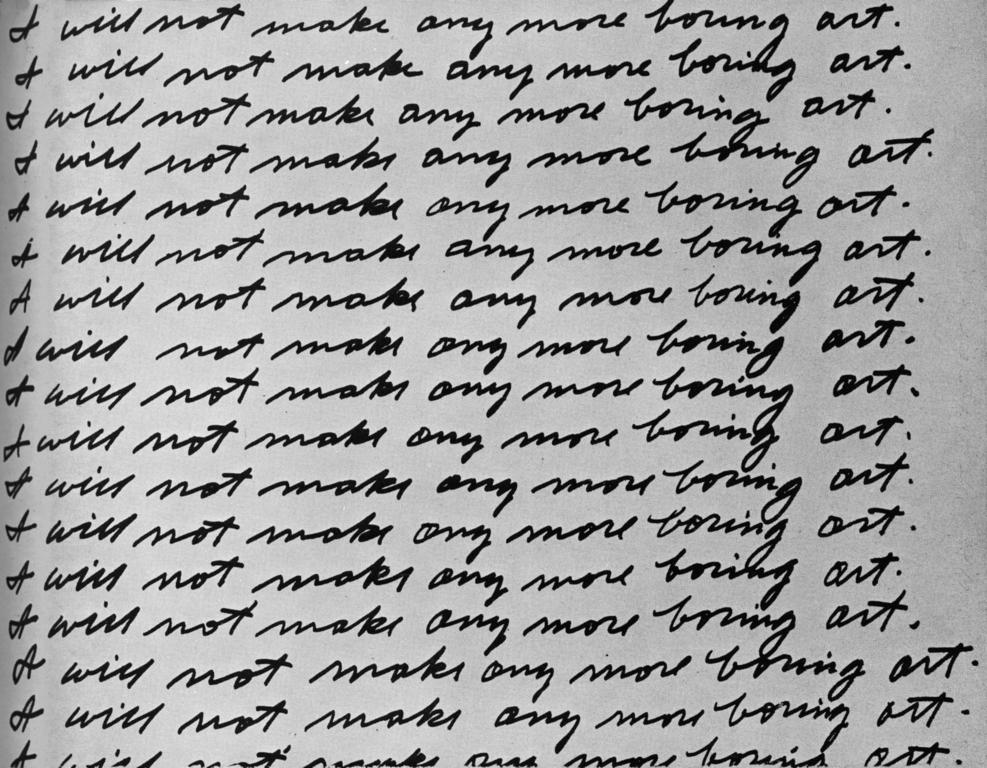

However, Hirst’s champions – and eventually, Hirst himself – shifted the mythology surrounding his practice. They argued that his true medium wasn’t preserved animal carcasses or mirrored cabinets filled with harlequin arrays of pills or any other tangible material that went into the creation of a physical artwork. His medium was the art market itself. With the fabric of Conceptual Art draped over his shoulders like a magician’s cape, he was conducting a kind of grand illusion before our eyes. Every new exhibition, every new interview, every new transmission from Hirst’s studio was just the next bit of sleight of hand, all of it building toward a grand finale greater than the sum of its parts.

But unlike a magician, Hirst’s performance was either an intentional farce, an open challenge, or both. Imagine that the entire point of the magic show is to give the audience the opportunity to recognize its fraudulence. At its core, the pro-Hirst argument was an argument for the artist as provocateur. His career could be read as a daily performance engineered to reveal the absurdities of the contemporary art market. He would do so by creating better and better traps to lure out the tastelessness and raw capitalist lust that fueled the industry. If you gave credence to the argument, Hirst was like the serial killer in David Fincher’s SE7EN. He turned the art world’s own sins and excesses back on it to teach the rest of us a lesson we wouldn’t be able to ignore. After all, what better indictment was there of the state of art than tricking a horde of Russian and Middle Eastern oligarchs to bid up a piece of taxidermy until it became a multi-million dollar asset?

Despite its staunch pro-Hirst-ness, this argument created a simple but catastrophic problem for Beautiful Inside My Head Forever. If his career was a performance aimed at reflecting the art world’s image back to itself, then that performance is what his many prominent dealers were choosing to represent when they brought Hirst on board at their galleries. Which in turn meant that they would have been working with Hirst to help evolve and strengthen that performance in any way they could. If that was the case, was it really plausible that the Sotheby’s sale was Hirst’s rebellion? Wasn’t it more likely an idea that had been conceived and carefully orchestrated by some of the industry’s savviest businessmen?

If the sale lived up to the rhetorical hype – if it truly became the prototype of a new business model – then it would indeed be historic. In fact, even if it was a financial sink hole, the Sotheby’s sale cemented Hirst’s status as an icon. A hundred years from now, it would be gross negligence to survey contemporary art in the aughts without mentioning Beautiful Inside My Head Forever. But massive success at this auction wouldn’t mean the immediate end of Hirst’s traditional gallery exhibitions. There simply wasn’t capacity for that on either Hirst’s end or Sotheby’s. Hirst’s studio produced too much work – and I would guess that they needed to, in order to bring in enough money to keep the machine going. Sotheby’s would have needed to expand its infrastructure substantially, to essentially create a venture dedicated solely to Hirst auctions. And of course, as soon as those auctions became standard practice, they – and the work that constituted them – would lose their luster. No, the Sotheby’s sale was a one-off event, and Gagosian, White Cube, and the others who represented Hirst all stood to benefit from it in kind. Didn’t that make collusion all the more probable?

Even denying the conspiracy theory didn’t remove the conflicts of interest. I mentioned earlier that auctions endanger everyone who collects or represents an artist. This fact becomes even truer at volume. The only thing worse than one piece’s underperforming is multiple pieces’ underperforming. Hirst consigned 223 works to Sotheby’s in one fell swoop. If Beautiful Inside My Head Forever tanked, Hirst’s entire market could collapse overnight. That held consequences not just for the new work – and thus, Hirst’s dealers – but for the earlier works as well – and thus, Hirst’s collectors. The more of his work one owned or controlled, the higher the stakes in the Sotheby’s sale. In that sense, it mattered very little whether the idea for the sale was Hirst’s alone or a collaboration between him and a cabal of elite dealers. Too many people had too much money riding on the outcome of the auction to let it fail. Hirst’s price points needed to be maintained.